Of all the postulates, Bohr made in his model of the atom, perhaps the most puzzling is his second postulate. It states that the angular momentum of the electron orbiting around the nucleus is quantised (that is, Ln = nh/2π; n = 1, 2, 3 …). Why should the angular momentum have only those values that are integral multiples of h/2π? The French physicist Louis de Broglie explained this puzzle in 1923, ten years after Bohr proposed his model.

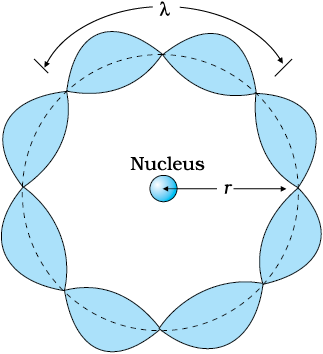

We studied, in Chapter 11, about the de Broglie’s hypothesis that material particles, such as electrons, also have a wave nature. C. J. Davisson and L. H. Germer later experimentally verified the wave nature of electrons in 1927. Louis de Broglie argued that the electron in its circular orbit, as proposed by Bohr, must be seen as a particle wave. In analogy to waves travelling on a string, particle waves too can lead to standing waves under resonant conditions. From Chapter 15 of Class XI Physics textbook, we know that when a string is plucked, a vast number of wavelengths are excited. However only those wavelengths survive which have nodes at the ends and form the standing wave in the string. It means that in a string, standing waves are formed when the total distance travelled by a wave down the string and back is one wavelength, two wavelengths, or any integral number of wavelengths. Waves with other wavelengths interfere with themselves upon reflection and their amplitudes quickly drop to zero. For an electron moving in nth circular orbit of radius rn, the total distance is the circumference of the orbit, 2πrn. Thus

2π rn = nλ, n = 1, 2, 3... (12.24)

Figure 12.10 illustrates a standing particle wave on a circular orbit for n = 4, i.e., 2πrn = 4λ, where λ is the de Broglie wavelength of the electron moving in nth orbit. From Chapter 11, we have λ = h/p, where p is the magnitude of the electron’s momentum. If the speed of the electron is much less than the speed of light, the momentum is mvn. Thus, λ = h/mvn. From Eq. (12.24), we have

2π rn = n h/mvn or m vn rn = nh/2π

This is the quantum condition proposed by Bohr for the angular momentum of the electron [Eq. (12.13)]. In Section 12.5, we saw that this equation is the basis of explaining the discrete orbits and energy levels in hydrogen atom. Thus de Broglie hypothesis provided an explanation for Bohr’s second postulate for the quantisation of angular momentum of the orbiting electron. The quantised electron orbits and energy states are due to the wave nature of the electron and only resonant standing waves can persist.

Bohr’s model, involving classical trajectory picture (planet-like electron orbiting the nucleus), correctly predicts the gross features of the hydrogenic atoms*, in particular, the frequencies of the radiation emitted or selectively absorbed. This model however has many limitations.

Some are:

Figure 12.10 A standing wave is shown on a circular orbit where four de Broglie wavelengths fit into the circumference of the orbit.

(i) The Bohr model is applicable to hydrogenic atoms. It cannot be extended even to mere two electron atoms such as helium. The analysis of atoms with more than one electron was attempted on the lines of Bohr’s model for hydrogenic atoms but did not meet with any success. Difficulty lies in the fact that each electron interacts not only with the positively charged nucleus but also with all other electrons.

* Hydrogenic atoms are the atoms consisting of a nucleus with positive charge+Ze and a single electron, where Z is the proton number. Examples are hydrogenatom, singly ionised helium, doubly ionised lithium, and so forth. In theseatoms more complex electron-electron interactions are nonexistent

The formulation of Bohr model involves electrical force between positively charged nucleus and electron. It does not include the electrical forces between electrons which necessarily appear in multi-electron atoms.

(ii) While the Bohr’s model correctly predicts the frequencies of the light emitted by hydrogenic atoms, the model is unable to explain the relative intensities of the frequencies in the spectrum. In emission spectrum of hydrogen, some of the visible frequencies have weak intensity, others strong. Why? Experimental observations depict that some transitions are more favoured than others. Bohr’s model is unable to account for the intensity variations.

Bohr’s model presents an elegant picture of an atom and cannot be generalised to complex atoms. For complex atoms we have to use a new and radical theory based on Quantum Mechanics, which provides a more complete picture of the atomic structure.