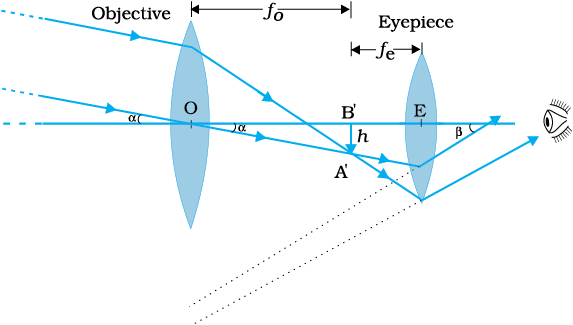

The telescope is used to provide angular magnification of distant objects (Fig. 9.32). It also has an objective and an eyepiece. But here, the objective has a large focal length and a much larger aperture than the eyepiece. Light from a distant object enters the objective and a real image is formed in the tube at its second focal point. The eyepiece magnifies this image producing a final inverted image. The magnifying power m is the ratio of the angle β subtended at the eye by the final image to the angle α which the object subtends at the lens or the eye. Hence

(9.46)

In this case, the length of the telescope tube is fo + fe.

Terrestrial telescopes have, in addition, a pair of inverting lenses to make the final image erect. Refracting telescopes can be used both for terrestrial and astronomical observations. For example, consider a telescope whose objective has a focal length of 100 cm and the eyepiece a focal length of 1 cm. The magnifying power of this telescope is m = 100/1 = 100.

Let us consider a pair of stars of actual separation 1′ (one minute of arc). The stars appear as though they are separated by an angle of 100 × 1′ = 100′ =1.67°.

The main considerations with an astronomical telescope are its light gathering power and its resolution or resolving power. The former clearly depends on the area of the objective. With larger diameters, fainter objects can be observed. The resolving power, or the ability to observe two objects distinctly, which are in very nearly the same direction, also depends on the diameter of the objective. So, the desirable aim in optical telescopes is to make them with objective of large diameter. The largest lens objective in use has a diameter of 40 inch (~1.02 m). It is at the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin, USA. Such big lenses tend to be very heavy and therefore, difficult to make and support by their edges. Further, it is rather difficult and expensive to make such large sized lenses which form images that are free from any kind of chromatic aberration and distortions.

Figure 9.32 A refracting telescope.

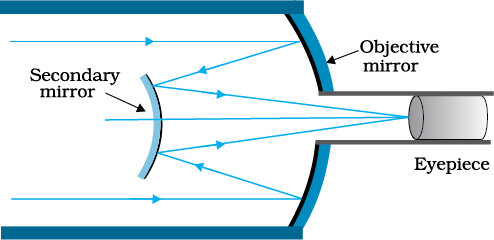

For these reasons, modern telescopes use a concave mirror rather than a lens for the objective. Telescopes with mirror objectives are called reflecting telescopes. There is no chromatic aberration in a mirror. Mechanical support is much less of a problem since a mirror weighs much less than a lens of equivalent optical quality, and can be supported over its entire back surface, not just over its rim. One obvious problem with a reflecting telescope is that the objective mirror focusses light inside the telescope tube. One must have an eyepiece and the observer right there, obstructing some light (depending on the size of the observer cage). This is what is done in the very large 200 inch (~5.08 m) diameters, Mt. Palomar telescope, California. The viewer sits near the focal point of the mirror, in a small cage. Another solution to the problem is to deflect the light being focussed by another mirror. One such arrangement using a convex secondary mirror to focus the incident light, which now passes through a hole in the objective primary mirror, is shown in Fig. 9.33. This is known as a Cassegrain telescope, after its inventor. It has the advantages of a large focal length in a short telescope. The largest telescope in India is in Kavalur, Tamil Nadu. It is a 2.34 m diameter reflecting telescope (Cassegrain). It was ground, polished, set up, and is being used by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore. The largest reflecting telescopes in the world are the pair of Keck telescopes in Hawaii, USA, with a reflector of 10 metre in diameter.